Yesterday would have been Anthony Bourdain’s 68th birthday. I often find myself reflecting on a rather famous quote of his:

“Travel isn't always pretty. It isn't always comfortable. Sometimes it hurts, it even breaks your heart. But that's okay. The journey changes you; it should change you.”

This sentiment encapsulates the difference between being a traveler and a tourist, a distinction that has become more poignant with each journey I take.

The main difference is this: tourists observe, and travelers experience.

The times that I have felt most like a traveler have been the times that I have gone off the grid in pursuit of connectivity to nature, the local community, and myself. For me, these experiences have usually come through the form of larger volunteer projects, where I’ve witnessed firsthand the way locals live through their triumphs and tribulations.

One such transformative journey was my visit to Tanzania right after I graduated college, back in 2017. On the way, my flight was canceled, and I found myself stuck in Istanbul. Alone at the age of 22, I made friends with total strangers in the visa line, visited mosques, and navigated through discomforting yet enriching situations in my 24 hours stuck in the city. I dealt with finding bloody sheets in the hotel room where the airline put me up. I dealt with not being able to find food easily during the day — I happened to be stuck there during Ramadan. I wouldn’t wish these experiences on anyone else necessarily, but I am appreciative of them, because they taught me the importance of grit and resilience when traveling. Up to that point, I had only been on overly-planned family vacations, where the biggest drama was having to share a pullout couch with my brother and fighting over what to watch on TV.

When I finally arrived in Tanzania, I embarked on hiking Mount Kilimanjaro, staying in huts with 20 other hikers who shared their lives and intricate stories with me. I attended a local bank meeting, learning about micro-loans that enabled locals to start their own banana farms. Eating local food (like goat with the hair and teeth still intact) and building accommodations for teachers at local schools connected me deeply to the community, because I gained a sliver of understanding for how they lived. I got to see their celebrations and successes, their pain and sadness, and the minutiae of their daily lives. Playing soccer with the local children, communicating through expressions and laughter rather than word is a memory etched into my heart. Camping in the middle of the savanna during hearing hyenas at night and being escorted to bathrooms with shotguns during our safari was both thrilling and humbling, and it was a good reminder that I was in the territory of Lions. That was their home, and I was a trespassing visitor. I wasn’t staying in a five star glamping tent, I was in the wild, and it felt raw and exciting.

This was the trip that taught me that there was a distinction between travel and vacation — the presence of tangible adventure versus the lack thereof.

Another recent unforgettable experience was volunteering in the remote region of Choco, Colombia, at Mama Orbe’s Eco Farm.

Mama Orbe is a family matriarch — she’s in charge of the Eco Farm where I stayed, and she’s the one making sure that local sea turtle conservation happens seamlessly, while taking care of her large family.

A quote from Mama Orbe herself:

“Human beings should not believe comments, they should give themselves the opportunity to get to know places for themselves and live their own experience of the place.”

And that’s exactly what I attempted to do while staying with her.

During my week in one of the more remote regions of Colombia, I helped install solar panels and a power grid to aid with her sea turtle conservation project. I got to witness firsthand local cooking and sustainability practices. We caught fish and ate it hours later — we had to, as there was no refrigeration, and no way to preserve simple items in a way that I had taken for granted. All of the produce was grown on property, down to the sugarcane they used. Talk about farm-to-table. We wrapped perishable food in husks and leaves to avoid single-use plastics. I slept in a hut with no air conditioning when it was 95 degrees out, with 100% humidity. I cried myself to sleep the first night, while I felt like I was choking on the thick air.

But then I remembered — the locals did this every single night. This was what they knew, this was their way of life. If they could do it, I could handle it for a week, and in handling it, I got to wake up on the most beautiful beach I’ve ever seen, miles and miles from civilization. I was far from home, but I had simultaneously never felt so at home, embraced by Mama Orbe and her family, as they welcomed us into their home, patiently feeding us and taking care of us in exchange for something I have always taken for granted as a basic human right — electricity.

I got to hear their stories and ways of life, and I got to celebrate with them when the lights came on for the first time. These are memories that I will cherish forever.

Both of these experiences challenged me and provided a deep appreciation for the resilience and ingenuity of the local communities, something I wouldn’t have gained if I hadn’t opened my mind and heart to fully experiencing the places I was going.

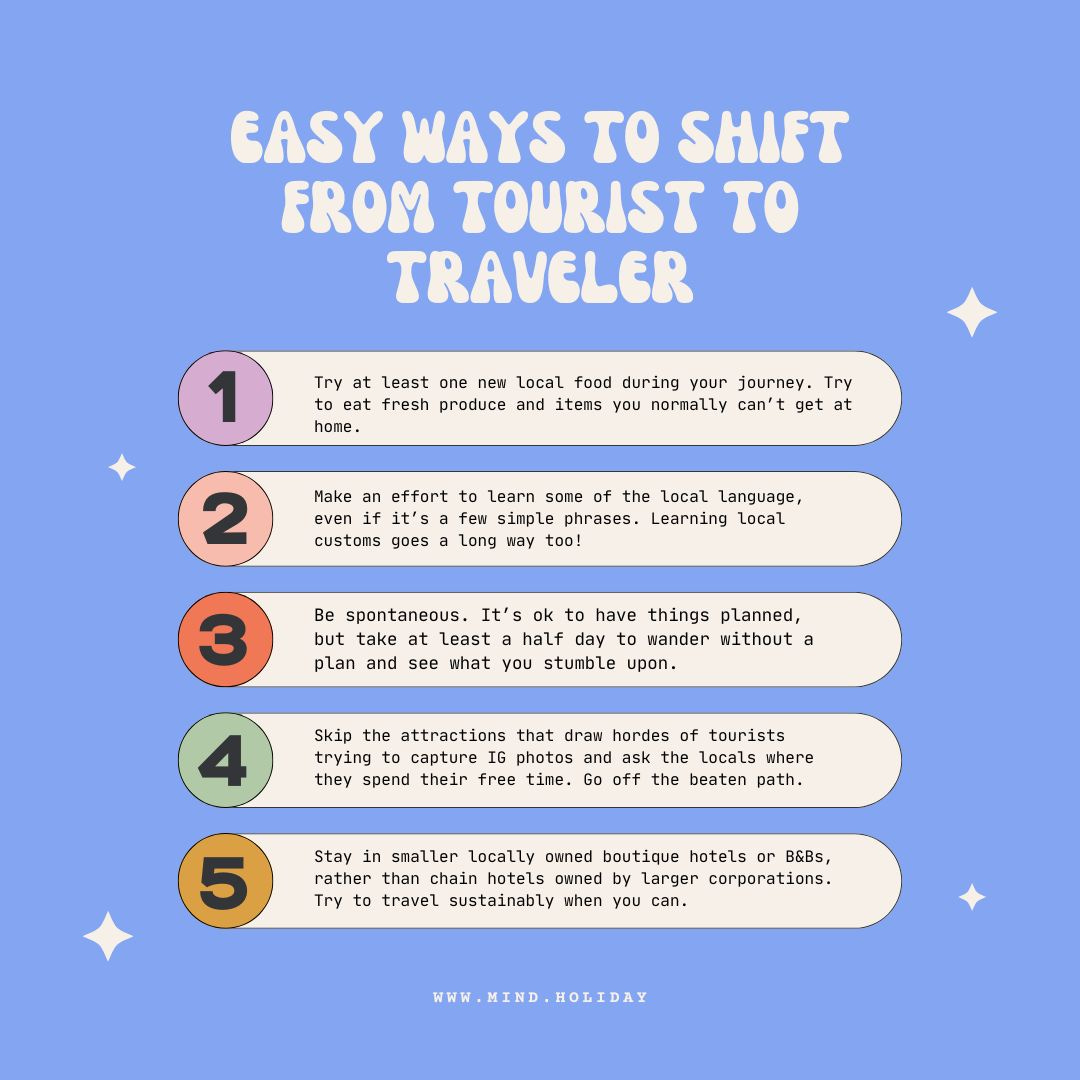

The Shift From Tourist to Traveler

The experiences I just described are BIG experiences, and I am not necessarily recommending that you start booking big, hairy, intimidating trips. You can make small changes to shift from tourist to traveler, and most of it comes down to self awareness and spontaneity.

Why should you change the way you think about travel? Because approaching a trip through the lens of a traveler (experiencing) rather than a tourist (observing) pays larger memory dividends.

An explanation from Noah Cracknell (although the concept of memory dividends comes from the book Die With Zero, which I recommend):

..Experiences have memory dividends.

A memory dividend is the re-experiencing of an experience. When you’re 90 years old, sitting with your lady happily sipping a cup of joe, you may think back to your early twenties when you stayed up all night in Barcelona — on the beach — drinking beers till sunrise with your buddies.

You’re re-experiencing a memorable night in Barcelona — one that you probably wouldn’t trade for anything. That’s a memory dividend. If you’ve ever shared an experience with someone and talked about it for weeks, months, or even years later, that’s also a memory dividend.

A traveler tries local cuisine, challenges themselves, and takes the road less traveled. They learn something new about their destination, whether it's phrases in the native language or general history. Travelers are mindful of their impact on the environment and local communities. They say yes to new and potentially scary things, whether it’s trying crickets, bull testicles, skydiving, or local adventures.

In contrast, a tourist often follows a prescribed path of guidebook highlights and Instagram hotspots. They might not seek out adventure or consider the impact of their travel on local communities. Typical tourist activities, like staying in all-inclusive resorts, mean you might never leave the comfort of the resort and miss out on experiencing local life. The best finds are often off the hop-on-hop-off bus path, and away from the top-rated restaurants on TripAdvisor. It’s the unplanned detours, the small, family-run eateries, and the spontaneous conversations that leave the most lasting impressions.

It’s important to note that I’m not a traveler all of the time, and I fall into the tourist bucket often. I often crave stumbling into the familiar when I am abroad, and I give myself permission to do so. You’re allowed to relax at a resort for a week if that’s what you need. You’re allowed to go to McDonalds when you’re homesick for comfort food. You’re allowed to see Big Ben and the Eiffel Tower.

It’s okay to be a tourist sometimes, but it's crucial to be aware of the role you play when traveling and how it can affect your overall understanding of the places you visit.

But keep in mind that the real growth and memory dividends come from discomfort and discovery — and make time for this too. It’s about surrendering to the unfamiliar, whether it's navigating a bustling market in Marrakech or getting lost in the winding alleys of Tokyo. This willingness to step outside our comfort zones is what transforms a trip into a transformative experience. It’s a reminder that the world is vast and varied, and that our understanding of it deepens with every step we take into the unknown. These moments of deep exposure are necessary.

Reflecting on my own travel experiences, I realize that the most profound and memorable moments weren't the ones meticulously planned, but rather the serendipitous encounters and uncharted adventures. It's the conversations with locals, the unplanned stops at roadside attractions, and the quiet moments of introspection that define us as travelers, not tourists. I also realize that it is a privilege to visit new places, and with that privilege, I personally feel responsible to make an effort to see new places through the lens of local eyes, rather than going into a new place with rigid expectations and a list of what everyone else has done.

By seeking out the authentic, the raw, and the real, we can open our hearts and minds to the joys that travel brings, understanding that it’s not just about the destination, but the journey itself. In doing so, we become not just visitors in foreign lands, but true explorers of the human experience.

I challenge you to go on your next trip with your heart, mind, and eyes wide open, even if it’s just for an afternoon. I bet you stumble upon something you never expected!

This was a great article. I have long held the same view. Traveling has made all the difference. :)

So insightful 👏👏 Btw, did you have any special training before climbing Mount Kilimanjaro? Would love to do the same one day